Fortress India

For Foreign Policy

Felani wore her gold bridal jewelry as she crouched out of sight inside the squalid concrete building. The 15-year-old’s father, Nurul Islam, peeked cautiously out the window and scanned the steel and barbed-wire fence that demarcates the border between India and Bangladesh. The fence was the last obstacle to Felani’s wedding, arranged for a week later in her family’s ancestral village just across the border in Bangladesh.

There was no question of crossing legally — visas and passports from New Delhi could take years — and besides, the Bangladeshi village where Islam grew up was less than a mile away from the bus stand on the Indian side. Still, they knew it was dangerous. The Indians who watched the fence had a reputation for shooting first and asking questions later. Islam had paid $65 to a broker who said he could bribe the Indian border guard, but he had no way of knowing whether the money actually made it into the right hands.

Father and daughter waited for the moment when the guards’ backs were turned and they could prop a ladder against the fence and clamber over. The broker held them back for hours, insisting it wasn’t safe yet. But eventually the first rays of dawn began to cut through the thick morning fog. They had no choice but to make a break for it.

Islam went first, clearing the barrier in seconds. Felani wasn’t so lucky. The hem of her salwar kameez caught on the barbed wire. She panicked, and screamed. An Indian soldier came running and fired a single shot at point-blank range, killing her instantly. The father fled, leaving his daughter’s corpse tangled in the barbed wire. It hung there for another five hours before the border guards were able to negotiate a way to take her down; the Indians transferred the body across the border the next day. “When we got her body back the soldiers had even stolen her bridal jewelry,” Islam told us, speaking in a distant voice a week after the January incident.

Other border fortifications around the world may get all the headlines, but over the past decade the 1,790-mile fence barricading the near entirety of the frontier between India and Bangladesh has become one of the world’s bloodiest. Since 2000, Indian troops have shot and killed nearly 1,000 people like Felani there.

In India, the 25-year-old border fence — finally expected to be completed next year at a cost of $1.2 billion — is celebrated as a panacea for a whole range of national neuroses: Islamist terrorism, illegal immigrants stealing Indian jobs, the refugee crisis that could ensue should a climate catastrophe ravage South Asia. But for Bangladeshis, the fence has come to embody the irrational fears of a neighbor that is jealously guarding its newfound wealth even as their own country remains mired in poverty. The barrier is a physical reminder of just how much has come between two once-friendly countries with a common history and culture — and how much blood one side is willing to shed to keep them apart.

The Godfather of Bangalore

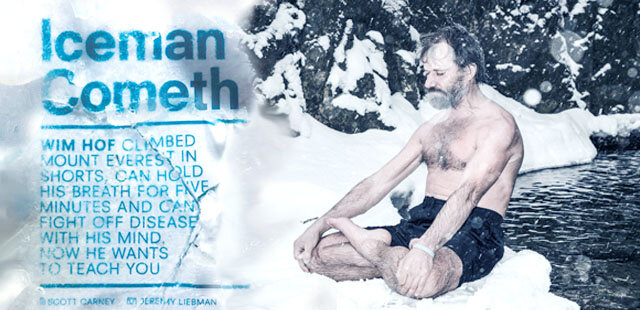

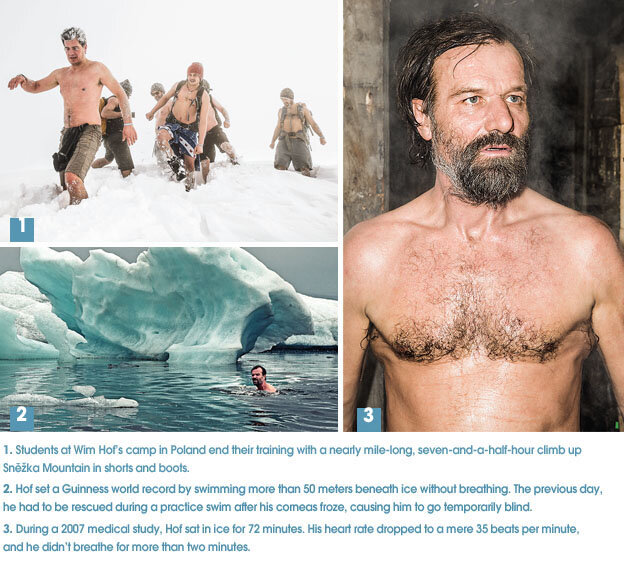

For Wired

Originally published in Wired.

It’s a little past midnight, and a lonely parcel of farmland not far from the new international airport in Bangalore, India, is soaking up a gentle rain. At the center of the lot is a house surrounded by a low stone wall. There’s a hole in the roof and a bushel of ginger drying under an awning. Large block letters painted on the wall read: THIS PROPERTY BELONGS TO CHHABRIA JANWANI. Inside, eight men—two armed with shotguns—confer in hushed voices as they peer out the windows. Is it safe for them to go to sleep, or should they stand watch another few hours? A guard wearing a dirty work shirt is the first to notice signs of trouble. In the distance, flashlight beams sweep the roadway. The lights advance, accompanied by a chorus of voices. Then the sound of people scrambling over the wall. One of the guards makes a break for the gate, sprinting toward a police station a mile away. Before the others can do much more than scramble to their feet, 20 attackers brandishing swords and knives emerge from the shadows. Some carry buckets of blue paint. It takes them only a minute to overrun the building. Three guards who stood their ground lie bleeding on the floor. The others surrender.

Firmly in control, the marauders shift gears. They pull out rollers and slather paint over Chhabria Janwani’s claim to the land. By the time a police jeep pulls up, the sign is only a memory. The attackers have achieved their goal. Thanks to the convoluted rules surrounding land ownership, the removal of Janwani’s lettering throws his claim into question. The dispute is no longer just a criminal matter of a gang of outlaws taking over a piece of ground; now it’s a civil issue that will have to be mediated in the courts. This kind of legal battle, with its near-endless appeal process, could easily last 15 years. If Janwani hopes to develop or sell the parcel during that time, he’d be better off just letting his assailants have the property in exchange for a fraction of its value.

Bangalore’s Mobster Turned Mogul: Muthappa Rai is an Indian real estate power broker. He used to be a mafia don, wanted for murder by the Indian police. Wired’s Scott Carney talks to the Bangalore land baron.

Bangalore, the fifth-most populous city in India, is the tech outsourcing capital of the world. In the past decade, more than 500 multinational corporations have established office parks, call centers, and luxury hotels here. The arrival of US companies like Adobe, Dell, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, and Yahoo, along with the emergence of homegrown outfits like Infosys and Wipro, has transformed this sleepy outpost into a premier showcase of globalism. Bangalore accounted for more than a third of India’s $34 billion IT export market in 2007. Upscale commercial spaces like UB Tower, modeled after the Empire State Building, and first-rate educational institutions like the Indian Institute of Science set the standard for what India could become.

But there’s a dark side to Bangalore’s rocket ride. City officials—at least those who aren’t taking bribes—struggle to reconcile the gleaming promise of the information economy with the gritty reality of systemic corruption, a Byzantine justice system, and a criminal underworld more than willing to maim and murder its way into control of the city’s real estate market. As tech companies gobble up acreage, demand has pushed prices into the stratosphere. In 2001, office space near the center of town sold for $1 a square foot. Now it can go for $400 a square foot. Janwani bought his 6-acre plot in 1992 for $13,000. Today, even undeveloped, it’s worth $3 million.

A guard carrying a short-barrel shotgun patrols the area around Muthappa Rai’s home.

Photograph: Scott Carney

But high prices are only part of the problem for businesses looking for space in the city. It’s nearly impossible to determine who actually owns any given piece of Bangalorean real estate. Some 85 percent of citizens occupy land illegally, according toSolomon Benjamin, a University of Toronto urban studies professor who specializes in Bangalore’s real estate market. Most land in the city, as in the rest of India, is bound by ancestral ties that go back hundreds of years. Little undisputed documentation exists. Moreover, as families mingle and fracture over generations, ownership becomes diluted along with the bloodline. A buyer who wants to acquire a large parcel may have to negotiate with dozens of owners. Disputes are inevitable.

That’s where Bangalore’s land mafia comes in. With the courts tied up in knots, gangsters offer to secure deeds in days rather than years. “Businesspeople like to do their business, but many times the system does not permit them to do it,” says Gopal Hosur, the city’s joint police commissioner. “Because of escalating land values, unscrupulous elements get involved. They use muscle power to take control of the land.” Some 40 percent of land transactions occur on the black market, according to Arun Kumar, an economist at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Often the local authorities facilitate these deals. A World Bank report rated the Bangalore Development Authority, which oversees urban planning, as one of the most corrupt and inefficient institutions in India.

Lokesh’s nickname, “Malama”, means “medicine”. As in if you have a problem, Lokesh is the medicine. He is a well-known rowdie who settles real estate deals with force.

Photos: Scott Carney

On the ground, violence is meted out by local toughs like “Mulama” Lokesh, whose first name means “medicine”—as in, if you have a problem, Lokesh has the cure. He’s an old-school gangster who happily shows off a bag full of curved swords called longs and cruel Chinese-made knives that he keeps in the trunk of his car. Despite a record of charges that include murder and extortion, even he is wistful for the old days. “The money is so big now that the value of human life has gone down,” he says. “Now people fight with guns.”

Foreign Investment in Bangalore (in millions).

Inspector S. K. Umesh holds a cell phone a few inches from his ear, eavesdropping on a conversation. Since he became a police inspector four and a half years ago, his district’s crime rate has plummeted by 75 percent. He’s killed five of the city’s most wanted criminals and caught more supari killers—contract hit men—than any other officer in Karnataka, the state in which Bangalore is located. Every few seconds, the wiretap emits a soft beep. Wrapping his hand over the receiver, he says, “Without surveillance, we wouldn’t be anywhere.”

Umesh estimates that Bangalore is home to nearly 2,000 gangsters, 90 percent of them vying for a stake in the real estate market. Calling up a file on his computer, Umesh scrolls through hundreds of mug shots, offering a running commentary on which subjects have committed murder.

Umesh points to a face on his screen: Muthappa Rai. Owing to a successful career as a mob don, Rai has a net worth measured in billions of dollars. Once he was among the most wanted men in India. Today he professes to have reformed, renouncing violence and founding a charitable organization. But he’s also in real estate.

“In a way, Rai is just like any other goonda in Bangalore,” Umesh says. Still, the mobster has made his mark on the city’s underworld. In the 1980s, land disputes were settled with fists, knives, swords, and bamboo canes. But after Rai’s arrival in the mid-’80s, guns became the weapon of preference. He often outsourced the violence to pros who learned their trade on the streets of Mumbai and dispatched their victims with firearms.

These curved swords known as “longs” and chinese knives came from the back of Lokesh’s trunk. He keeps them on hand just in case he, or his men, have to use them.

Photograph: Scott Carney

“He started out with a few card parlors and cut his teeth killing the leaders of rival gangs” Umesh says. Rai murdered a rival in an early ’90s drive-by shooting, the inspector explains. Then he fled to Dubai, where he continued his operations. As the price of real estate back home began to take off, he paid $75,000 for the murder of a developer named Subbaraju who refused to sell a plot of land that Rai wanted. The lot would have become an upscale mall had not the hired assassin dropped his cell phone at the scene with Rai’s Dubai number on redial. Later, the killer fingered Rai as his employer. Rai admitted ordering the hit to a Bangalore news reporter.

In 2001, Interpol issued a Red Notice—essentially an international arrest warrant—for Rai’s extradition. Umesh flew to Dubai to help. The Dubai police nabbed Rai at his home, which had two Mercedes-Benzes parked outside, one red and one purple.

“But none of this matters,” Umesh says. “The court acquitted him, and in India there is no such thing as double jeopardy.” How could such a tightly wrapped case unravel? “It is very difficult to move things in our judicial system,” Umesh says. Moreover, testimony can be hard to come by. “There were lots of things going on: intimidation, tampering with witnesses.” Few victims of mob violence will speak out, for fear of further harm. Witnesses are threatened; judges are afraid to try powerful mobsters.

I meet with Subbaraju’s son, Jagdish Raju, a few blocks from where his father was killed, at an office building he leases to the government. His eyes fill with tears. “How can we fight the Muthappa Rais of the world?” he asks. “There was no use. What’s done is done.”

Umesh takes such hopelessness in stride. “Police work is like a sport,” he observes. His job is to bring criminals to court, but he holds little hope of seeing them convicted.

Two burly men carrying shotguns smile grimly as I drive past the first checkpoint to Muthappa Rai’s fortified compound. I’m an hour south of Bangalore in a patchwork of fallow fields and construction sites. Rai’s mansion comes into view at the top of a hill, a giant white building surrounded by a 20-foot-high concrete wall.

At the gate, armed security guards frisk me. They inspect my digital recorder to be sure it’s not a bomb. A golf cart carries me over an intricate driveway of cut brick. Hopping out at the front door, I step onto a floor of polished Italian marble.

Rai’s home is immense and gaudy, replete with gold ornaments and crystal chandeliers. Though he spends almost all his time here, the house feels eerily unlived-in, like a hotel lobby, as a platoon of servants keeps every surface shining. In the garage sits a bulletproof Land Cruiser. An attendant tells me Rai outbid Nawaz Sharif, the former prime minister of Pakistan, for it. The vehicle is built to withstand AK-47 bullets and rocket-propelled grenades.

Muthappa Rai says that he has reformed from a life of organized crime and is now a social worker and real estate developer.

Photograph: Scott Carney

Rai greets me with a charismatic grin. I ask about the need for such high security. “I am suffering for all of the things I did in my past,” he says. “I can’t trust anyone, not the government and certainly not my old enemies.” In 1994, in court on extortion charges, Rai was shot five times by a gunman dressed as a lawyer. Although he managed to beat the rap, he languished in bed for two years. The man who hired Rai’s assailant wasn’t so lucky; he was gunned down while the don lay in his sickbed. Did Rai order retaliation? He lets out a hearty laugh. “Five bullets,” he says cryptically.

But those days are behind him, he says. He has reinvented himself as a champion of Karnataka’s downtrodden. The primary layer in Rai’s veneer of respectability is Jaya Karnataka, a nonprofit social services organization with political overtones that, according to its Web site, appeals to a “universal order based on principles of human dignity, solidarity of people, and freedom of communication.” Jaya Karnataka runs free health camps around the state, digs wells in drought-stricken areas, and funds cataract and open-heart surgeries for the poor. Since Rai founded the group 18 months ago, membership has swelled to 700,000 in more than 300 branches across the state. Many people assume the group is Rai’s first sally in an upcoming bid for public office.

The organization also serves as a storefront for Rai’s main line of work: real estate. “When a foreign company wants to set up a business, they don’t know who to trust,” he says. “They need clear titles, and if they go to a local person, they’re going to get screwed with legal cases. But if Rai gives you a title, it comes with a 100 percent guarantee of no litigation. No cheating. It’s perfectly straightforward.” On any given day, he says, 150 people make their way to his opulent mansion to seek his help. He declines to name clients—association with his name might be bad for their business—but he lets slip that he recently acquired 200 acres of land for the titanic Indian conglomerate Reliance. A US firm looking to rent or buy might also go through Rai, but not directly. A facilities administrator in Bangalore—probably Indian—would work with a developer who, in turn, would contact Rai to secure a plot. “There’s no question of American companies coming to buy land,” he says.

Two guards armed with shotguns protect the front gate to Rai’s mansion.

Photograph: Scott Carney

According to a lawyer who deals with land issues, the system works like this: Asked to intercede by a prospective buyer, Rai checks out the parcel for competing owners. If two parties assert ownership, he hears both sides plead their case and decides which has the more legitimate claim (what he calls “80 percent legal”). He offers that person 50 percent of the land’s current value in cash. To the other, he offers 25 percent to abandon their claim—still a fortune to most Indians, given the inflated price of Bangalorean real estate. Then he sells the land to his client for the market price and pockets the remaining 25 percent. Anyone who wants to dispute the judgment can take it up with him directly.

Rai’s lieutenant, Sangeeth—who prefers to be identified as the boss’s “blue-eyed boy”—says that violence is almost never an issue. “All anyone needs to hear is his name,” he says. “If a rowdy won’t back down, then we go to the person who is behind him and cut it off at the spine,” Sangeeth explains. “In the hypothetical instance where it does need to come to violence, someone might need to be beaten up. The next day we would leave a message that we were behind it and that this was just a warning. The name alone has power.”

Paradoxically, Rai’s strong-arming may be helping to curb violence in Bangalore. With a system in place—even a corrupt system—everyone knows how the game is played. As a result, fewer people get hurt. Or, as Rai would have it, “ultimately, everyone wants to settle. No one wants to go to the courts.”

Traffic and land mafia are some of hottest political issues in Bangalore. Anti-corruption candidates routinely target both for votes.

Photograph: Scott Carney

India’s judicial system may be convoluted, but it’s not as corrupt as its law enforcement agencies. In August 2008, Bangalore’s new police commissioner issued a memo to police stations trying to rein in widespread corruption. The circular begins: “It is alleged repeatedly in the press, as well as by the members of the public, and the floor of the legislature, that police officers have converted their police stations in Bangalore city as offices to settle land disputes and are taking huge amounts of illegal gratification. This does not augur well for our department.” The next 16 pages are filled with instructions for handling suspected mob activity and land disputes. Officers are threatened with strict censure if they fail to comply. Unfortunately, the guidelines are toothless because the department has yet to find an effective way to police the police.

Collusion between enforcers and mobsters raises troubling questions about the future of this city. “Since Bangalore went global, things have gotten worse,” says Santosh Hegde, his graying hair dyed jet-black and a chain of prayer beads around his neck. He’s the state official responsible for prosecuting corruption cases. “Businesspeople want to get things done quickly, and they have no option but to bribe officials to shortcut the bureaucracy,” he says.

Hegde, 68, served six years on India’s Supreme Court before taking the anticorruption beat. He oversees a team of accountants who burrow through documents and field operatives trained in covert recordings and sting operations. Since assuming office, Hegde has charged more than 300 officials with receiving cash bribes totaling over $250,000 and illegal assets and land holdings worth $40 million. That’s just 5 percent of total bribery in Karnataka, he says, which he estimates at more than $800 million. When we meet, local newscasters are reporting his latest triumph: the arrest of five civil servants who had allegedly collected $1.5 million in illegal assets and cash.

A painted over sign to Chhabria Jarwani’s land. Three days before this picture was taken, a gang of almost 40 men stormed this plot of land and took it over. Their first action was to paint over the owner’s name in order to orchestrate a false legal claim against him.

Photograph: Scott Carney

Hegde blames the avalanche of corruption on the outsourcing boom. “Certainly IT companies contribute to the problem,” he says. “They work with people who have only a shady title to the land. Then they occupy buildings that are constructed illegally, without permission from the authorities. I don’t want to name specific firms, but huge companies build illegally here.”

Hegde lodges a new case almost every day, but the power of his office is limited. To bring a case to court, he needs permission from what regulations call “the competent authority.” This usually means the malefactor’s superior officer, who has little motivation to expose corruption within his own department.

Hegde has reviewed two complaints that mention Muthappa Rai. In one case, a landowner alleged that Rai’s men tried to intimidate him into selling a lot in Electronics City, a Bangalore suburb packed with IT companies. He asked the police for protection. “The officer told him that it was best to settle—an obvious case of corruption,” Hegde says. “We began an investigation, and suddenly the man who filed the complaint disappeared. We had to close the case.”

Still, Hegde remains hopeful—and defiant. “I have lived a full life already,” he says. “If they kill me, I will die happy. And if Muthappa Rai gets public office, he’ll be under my jurisdiction,” he adds with a wry smile.

Back in his mansion on the outskirts of Bangalore, Rai stretches out on a leather sofa and smiles. “Foreign companies come in and everything improves,” he says. “I have seen this happen the whole world over. Now I’m helping make it happen here.”

Fire in the Hole

For Foreign Policy

by Jason Miklian and Scott Carney

Originally published in Foreign Policy Sept/Oct 2010

The richest iron mine in India was guarded by 16 men, armed with Army-issued, self-loading rifles and dressed in camouflage fatigues. Only eight survived the night of Feb. 9, 2006, when a crack team of Maoist insurgents cut the power to the Bailadila mining complex and slipped out of the jungle cover in the moonlight. The guerrillas opened fire on the guards with automatic weapons, overrunning them before they had time to take up defensive positions. They didn’t have a chance: The remote outpost was an hour’s drive from the nearest major city, and the firefight to defend it only lasted a few minutes.

The guards were protecting not only $80 billion-plus worth of mineral deposits, but also the mine’s explosives magazine, which held the ammonium nitrate the miners used to pulverize mountainsides and loosen the iron ore. When the fighting was over and the surviving guards rounded up and gagged, about 2,000 villagers who had been hiding behind the commando vanguard clambered over the fence into the compound and began emptying the magazine. Altogether they carried out 20 tons of explosives on their backs — enough firepower to fuel a covert insurgency for a decade.

Four and a half years after the attack in the remote Indian state of Chhattisgarh, the blasting materials have spread across the country, repackaged as 10-pound coffee-can bombs stuffed with ball bearings, screws, and chopped-up rebar. In May, one villager’s haul vaporized a bus filled with civilians and police. Another destroyed a section of railway later that month, sending a passenger train careening off the tracks into a ravine. Smaller ambushes of police forces on booby-trapped roads happen pretty much every week. Almost all of it, local police told us, can be traced back to that February night.

The Bailadila mine raid was one of India’s most profound strategic losses in the country’s protracted battle against its Maoist movement, a militant guerrilla force that has been fighting in one incarnation or another in India’s rural backwaters for more than 40 years. Over the course of the half-dozen visits we’ve made to the region during the past several years, we’ve come to consider the attack on the mine not just one defeat in the long-running war, but a symbolic shift in the conflict: For years, the Maoists had lived in the shadow of India’s breakneck modernization. Now they were thriving off it.

Only a decade ago, the rebels — often, though somewhat inaccurately, called Naxalites after their guerrilla predecessors who first launched the rebellion in the West Bengal village of Naxalbari in 1967 — seemed to have all but vanished. Their cause of communist revolution looked hopelessly outdated, their ranks depleted. In the years since, however, the Maoists have made an improbable comeback, rooted in the gritty mining country on which India’s economic boom relies. A new generation of fighters has retooled the Naxalites’ mishmash of Marx, Lenin, and Mao for the 21st century, rebranding their group as the Communist Party of India (Maoist) and railing against what the rebels’ spokesman described to us as the “evil consequences by the policies of liberalization, privatization, and globalization.”

Although it has gotten little attention outside South Asia, for India this is no longer an isolated outbreak of rural unrest, but a full-fledged guerrilla war. Over the past 10 years, some 10,000 people have died and 150,000 more have been driven permanently from their homes by the fighting. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told a high-level meeting of state ministers not long after the Bailadila raid that the Maoists are “the single greatest threat to the country’s internal security,” and in 2009 he launched a military surge dubbed “Operation Green Hunt”: a deployment of almost 100,000 new paramilitary troops and police to contain the estimated 7,000 rebels and their 20,000-plus — according to our research — part-time supporters. Newspapers run stories almost daily about “successful operations” in which police string up the bodies of suspected militants on bamboo poles and lay out their captured caches of arms and ammunition. Many of the dead are civilians, and the harsh tactics have polarized the country.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way — not in 21st-century India, a country 20 years into an experiment in rapid, technology-driven development, one of globalization’s most celebrated success stories. In 1991, with India on the brink of bankruptcy, Singh — then the country’s finance minister — pursued an ambitious slate of economic reforms, opening up the country to foreign investment, ending public monopolies, and encouraging India’s bloated state-run firms to behave like real commercial ventures. Today, India’s GDP is more than five times what it was in 1991. Its major cities are now home to an affluent professional class that commutes in new cars on freshly paved four-lane highways to jobs that didn’t exist not so long ago.

But plenty of Indians have missed out. Economic liberalization has not even nudged the lives of the country’s bottom 200 million people. India is now one of the most economically stratified societies on the planet; its judicial system remains byzantine, its political institutions corrupt, its public education and health-care infrastructure anemic. The percentage of people going hungry in India hasn’t budged in 20 years, according to this year’s U.N. Millennium Development Goals report. New Delhi, Mumbai, and Bangalore now boast gleaming glass-and-steel IT centers and huge engineering projects. But India’s vast hinterland remains dirt poor — nowhere more so than the mining region of India’s eastern interior, the part of the country that produces the iron for the buildings and cars, the coal that keeps the lights on in faraway metropolises, and the exotic minerals that go into everything from wind turbines to electric cars to iPads.

If you were to lay a map of today’s Maoist insurgency over a map of the mining activity powering India’s boom, the two would line up almost perfectly. Ground zero for the rebellion lies in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, a pair of neighboring, mostly rural states some 750 miles southeast of New Delhi that are home to 46 million people spread out over an area a little smaller than Kansas. Urban elites in India envision them as something akin to Appalachia, with a landscape of rolling forested hills, coal mines, and crushing poverty; their undereducated residents are the frequent butt of jokes told in more fortunate corners of the country.

Revenues from mineral extraction in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand topped $20 billion in 2008, and more than $1 trillion in proven reserves still sit in the ground. But this geological inheritance has been managed so disastrously that many locals — uprooted, unemployed, and living in a toxic and dangerous environment, due to the mining operations — have thrown in their lot with the Maoists. “It is better to die here fighting on our own land than merely survive on someone else’s,” Phul Kumari Devi told us when we visited her dusty mining village of Agarbi Basti in June. “If the Maoists come here, then we would ask their help to resist.”

The mines are also cash registers for the Maoist war chest. Through extortion, covert attacks, and plain old theft, insurgents have tapped a steady stream of mining money to pay their foot soldiers and buy arms and ammunition, sometimes from treasonous cops themselves. The result is the kind of perpetual-motion machine of armed conflict that is grimly familiar in places like the oil-soaked Niger Delta, but seems extraordinary in the world’s largest democracy.

This isn’t just an Indian story — it’s a global one. In the wake of Singh’s economic reforms, foreign investment in the country has grown to 150 times what it was in 1991. Among other things, India has opened up its vast mineral reserves to private and international players, and now major global companies like Toyota and Coca-Cola rely on mining operations in the heart of the Maoist war zone. Investors in the region claim that the fighting is taking a toll on their businesses, and Bloomberg News recently estimated that some $80 billion worth of projects are stalled at least in part by the guerrilla war, enough to double India’s steel output.

But in our visits to the region and dozens of interviews there — with miners and politicians, refugees and paramilitary leaders, cops and go-betweens for the guerrillas — we found a far more complex reality. Mining companies have managed to double their production in the two states in the past decade, even as the conflict has escalated; the most unscrupulous among them have used the fog of war as a pretext for land grabs, leveling villages whose residents have fled the fighting. At the same time, the Maoists, for all their communist rhetoric, have become as much a business as anything else, one that will remain profitable as long as the country’s mines continue to churn out the riches on which the Indian economy depends.

The first sign you see as you leave the airport in Jharkhand’s capital city of Ranchi welcomes you to the “Land of Coal,” and indeed, mining underlies every aspect of life here. Seams of coal are visible in the earth alongside the rutted roads that connect the jungle hamlets. Travelers learn to anticipate mines not by any road signs, but by the processions of men pushing bicycles heaped with burlap sacks full of coal: day laborers who pay for the opportunity to scrape the stuff out of thousands of off-the-books mines and sell it door to door as heating fuel, for perhaps a few more dollars a day than they would make as farmers trying to eke out a living from Jharkhand’s depleted soil.

India’s coal country was mostly passed over by British colonists until they discovered its mineral wealth in the late 19th century and built the obligatory handful of dusty frontier towns and roads necessary to take advantage of it. Today the region bears the obvious scars of a hundred-odd years of heavy industry. The damage is most visible at road marker 221 of Jharkhand’s main north-south highway, about 40 miles outside Ranchi, where a freshly paved patch of asphalt veers sharply west and snakes up a smoky hill through the village of Loha Gate and into an ecological disaster zone. Shimmering waves of heat, thick with carbon monoxide and selenium, waft through jagged cracks in the pavement large enough to swallow a soccer ball. A hundred feet below, a massive subterranean coal fire, started in an abandoned mine, burns so hot that it melts the soles of one’s shoes. The only vestiges of plant life are the scattered hulks of desiccated trees. Like the legendary coal fire that destroyed Centralia, Pennsylvania, this blaze could easily smolder for another 200 years before the coal seam is finally burned through.

There are at least 80 coal fires like this burning in Jharkhand, turning much of the state’s ground into a giant combustible honeycomb. A fire ignited in 1916 by neglectful miners near the city of Jharia has grown so large that it now threatens to burn away the land beneath the entire community, plunging the 400,000 residents into an underground inferno. One mine just outside Jharia collapsed in 2006, killing 54 people.

Coal mining and armed rebellion have long gone hand in hand in what is now Jharkhand, both dating back to the mid-1890s, when the British began extracting coal from the area and Birsa Munda, today a local folk hero, launched a tribal revolt to regain local control of resources. The British quelled the uprising with a massive deployment of troops, but the resentment festered. India’s government after independence proved a poor landlord as well, with decades of mining disasters — more than 700 people were killed in them between 1965 and 1975 alone — and a corrupt, nearly feudal government that made what was then the state of Bihar notorious in India as the country’s most poorly run, backward region.

By the 1990s, fed-up residents campaigned to carve Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh into their own jurisdictions. The politicians behind the movement argued that the people who lived in the shadow of the mines were the least likely to benefit from them, the spoils instead accruing to large out-of-state corporations and venal government officials in distant capitals. In 2000, India’s Parliament acquiesced, forming new states that then-Home Minister L.K. Advani declared would “fulfill the aspirations of the people.”

But statehood only enabled the rise of a new cast of villains. Absentee political landlords were replaced with home-grown thugs who exploited the new state government’s lax oversight to build their own fiefdoms. Madhu Koda, one of Jharkhand’s former chief ministers, is awaiting trial on allegations he siphoned $1 billion from state coffers — an astonishing 20 percent of the state’s revenues — during his two-year tenure. Mining operations, fast-tracked without regard for environmental or safety concerns, expanded at an alarming rate and are now projected to displace at least half a million people in Jharkhand by 2015.

The blighted landscape has proved to be fertile ground for the Maoist insurgency’s renaissance. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Maoists’ predecessors in the Naxalite movement had waged a bloody revolutionary campaign across rural India, only to mostly fade away by the early 1990s. The Maoists who have picked up the Naxalites’ banner in recent years are different, and the contours of their rebellion are hard to pin down.

These fighters claim to be led in battle by an elusive figure called Kishenji, who depending on whom you ask is either a one-legged, battle-hardened Brahmin, a 1960s-era radical with a Ph.D. from New Delhi, or simply a moniker used by anyone within the organization who wishes to sound authoritative or confuse the police. The guerrillas shun email and mobile phones and rarely communicate with the world beyond the jungle, mostly via letters ferried back and forth by foot soldiers. Over several years of attempted correspondence, we received only a few missives in return. All were written in an opaque style full of the sort of arcane Marxist jargon that the rest of the world forgot in the 1970s.

Today’s Maoists maintain the radical leftist politics of their predecessors and draw their civilian support from the same rural grievances — poverty, lack of justice, political disenfranchisement. But they are less an organized ideological movement than a loose confederation of militias, and many of their local commanders appear to be in it for the money alone. They wage war sporadically across a 1,000-mile swath of India, operating without a permanent base, relying on the tacit support of villagers to evade the police and paramilitary forces that hunt them, and periodically raiding remote police stations for resupplies of arms and ammunition.

But the rebels’ primary revenue comes from the region’s mines. Where the Naxalites used to congregate in areas with longstanding conflicts between landowners and laborers, Maoist strongholds now tend to pop up within striking distance of large-scale extractive operations. Such mines cover vast areas and are difficult to secure, making them sitting ducks for well-armed insurgents. “Most of the mines in this state are in the forests, so we are easy targets,” says Deepak Kumar, the owner of several such mines in Jharkhand. “The only way to stop the attacks is to negotiate.”

Kumar comes from a long line of Jharkhandi robber barons. In the 1980s, he used his mining camps as staging grounds for stalking the region’s near-extinct Bengal tigers. Today he owns a series of profitable but (by his own admission) illegal coal mines, hidden in the palm forests. Legal mines extract ore with giant machines that carve craters to the horizon; Kumar’s are more like secret caves, the coal dug out of deep tunnels with pickaxes by day laborers working for $2 to $3 a day. He told us his revenues run about $4 million a year, typical for off-the-books operations in a state where less than half of raw materials are extracted legitimately.

On July 4, 2004, Kumar was closing out the day’s accounts in his makeshift office at one of his mines when seven female guerrillas carrying automatic rifles broke down his door, forcing him into the forest at gunpoint. They marched him to a riverbed, where they stopped and held a gun to his head. “I thought I was going to die,” he recalls. Instead they demanded $2.5 million for his ransom.

Through the night, the Maoists marched him barefoot over crisscrossing trails, until they happened across a police patrol that was searching for him. Kumar escaped in the ensuing gun battle. But after he returned to work several weeks later, Maoist negotiators knocked on his door and let him know he was still a target. So, Kumar told us, he quickly hashed out a business arrangement with the rebels: In exchange for their leaving his operation alone, he would pay them 5 percent of his revenues.

The protection money, like the small bribes Kumar says he pays to the police to avoid troublesome safety and environmental regulations, has simply become another operating cost. Kumar says that every mine owner he knows pays up, too. By his back-of-the-envelope approximation, if the other estimated 2,500 illegal mines in the state are doling out comparable kickbacks to the rebels, the Maoists’ annual take would come to $500 million — enough to keep a militant movement alive indefinitely. “It works like a tax,” he says with a Cheshire grin, “just another business expense and now everything runs smoothly.”

Calls by politicians to clamp down on the Maoists’ extortion racket ring hollow as long as the politicians themselves are running the same sort of scheme — and in Jharkhand, they often are. Shibu Soren, a former national minister for coal and chief minister of Jharkhand until he was removed from office in May, has been tried for murder three times, though he was ultimately acquitted. (The crimes’ witnesses had a habit of disappearing, or turning up dead.) Last year, local newspapers exposed a case in which two henchmen of another local politician assassinated a children’s development aid worker, reportedly because he refused to pay the obligatory 10 percent kickback of his dairy goods after receiving a government contract. What they would have done with 3,000 gallons of milk is anyone’s guess.

“If you want to be somebody in Jharkhand, just kill an aid worker,” T.P. Singh, a Jharkhand correspondent for the Sahara Samay cable network, told us. A large man with a thick mustache, a TV-ready cocksure grin, and a penetrating stare, Singh is the network’s crime and corruption exposé king, and a celebrity in the region. He plays the role of the TV cowboy to the hilt, right down to the ubiquitous ten-gallon hat he was wearing when we met him at the local press club in the Jharkhandi mining city of Hazaribagh to ask about the dangers of reporting on powerful people in a land with no effective laws.

“You know how I get those boys to respect me?” Singh replied. “With this.” He reached into the waistband underneath his knee-length kurta and pulled out a Dirty Harry six-shooter, loaded and ready for action. A former Maoist turned politician, sitting on a couch across from Singh awaiting an interview, nodded his solemn approval.

The act is part bluster, but also part necessity. Many of Singh’s media compatriots in Jharkhand have been killed, kidnapped, or threatened with death by the Maoists, miners, politicians, or all three at some point in their careers. In some areas, local law enforcement has simply ceded authority to government-sanctioned civilian militias, which are often accused by locals of pillaging even more rapaciously than the Maoists — and contributing to the fighting by arming poor villagers. The most feared among them is Salwa Judum, secretly assembled by the Chhattisgarh government in 2005 to fight the Maoists; its 5,000-odd members patrol the state armed with everything from AK-47s to axes. Some roam the forest with bows and arrows.

“The Maoists have been killing locals for years,” Mahendra Karma, the founder of Salwa Judum, told us. “But when [Salwa Judum members] kill Maoists or Maoist supporters, all of a sudden people shout the word ‘human rights.’ There should be no double standard. If we kill a Maoist, then how is that a violation of human rights?”

Karma has the thick frame and round face of a heavyweight boxer a decade past his prime. When we met him in his office, far from the fighting, in Chhattisgarh’s capital of Raipur, he was flanked by armed guards. Above his desk was a life-size portrait of Mahatma Gandhi.

Karma founded the militia in 2005, when he was opposition leader in the state parliament. In the years since, he has presided over his district’s descent into a war zone, as the Maoists and Salwa Judum have taken turns torching villages and raping and killing hundreds of people each year in a spiral of revenge attacks. Some villages have been attacked more than 15 times by one side or the other. Salwa Judum members are also accused of extracurricular killing to settle personal scores, even dressing the bodies in Maoist uniforms to cover up their crimes.

When we met, Karma was happy at first to talk about the militia. But when our questions turned probing, his mood soured. Finally, rising to his feet and jabbing his finger into our chests, he shouted, “These questions you ask have come from the Naxalites — you are the men of the Naxalites!” In Chhattisgarh, Karma’s rage could easily amount to an extrajudicial death sentence. We were on the first flight back to Delhi.

It was just as well because by that point our attempts to contact anyone in the Maoist rebel camps had yielded next to nothing. After leftist author Arundhati Roy paid a visit to the Maoists this year, the Indian government reinterpreted its anti-terrorism laws to make speaking favorably about the rebels or their ideological aims — including opposition to corporate mining — punishable by up to 10 years in prison. This has made the Maoists’ civilian allies cagey about dealing with outsiders, and the already reclusive fighters even more difficult to reach. After months of sporadic contact with the Maoists’ liaisons, exchanging handwritten notes with couriers who arrived at our Ranchi hotel in the middle of the night, we made a breakthrough: Finally, a rebel spokesman by the nom de guerre of Gopal offered the prospect of visiting a Maoist camp. It would involve being whisked deep into the jungle on the back of a motor scooter and then camping out there for several days, waiting for the rebels to make contact, blindfold us, and take us the rest of the way to their outpost. We were ready to do it, but monsoon rains and a Green Hunt military offensive eventually scotched the plan.

Since then, the Maoists have kept busy. In addition to the May bus explosion near Bailadila that killed 35 people, the passenger-train derailment that same month killed almost 150 people, bringing total casualties to more than 800 so far in 2010 alone. The central government has responded by dispatching even more military resources to the area.

In a sense, however, India has already lost this war. It has lost it gradually, over the last 20 years, by mistaking industrialization for development — by thinking that it could launch its economy into the 21st century without modernizing its political structures and justice system along with it, or preventing the corruption that worsens the inequality that development aid from New Delhi is supposed to rectify. The government is sending in Army advisors and equipment — for now, the war is being fought by the Indian equivalent of a national guard, not the Army proper — and spending billions of dollars on infrastructure projects in the districts where the Maoists are strongest. But it hasn’t addressed the concerns that drove the residents of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand into the guerrillas’ arms in the first place — concerns that are often shockingly basic.

In the town of Jamshedpur we visited Naveen Kumar Singh, a superintendent of police who can boast of a string of hard-won victories over the Maoists, which include demolishing training camps, confiscating weapons, and racking up a double-digit body count. But Singh is also responsible for winning his district’s hearts and minds. When we stopped by his office, 10 petitioners were lined up in front of his desk. They were mostly poor men and women from rural areas, their clothes dusty from long bus rides. One woman in a purple sari arrived with a limp, leaning heavily on her son’s shoulders. She asked Singh for help moving forward a police investigation into the car that hit her. Everyone in the room knew that without his signature on her crumpled forms, nothing would happen.

But Singh looked bored and sifted idly through the woman’s handwritten papers. Finally, he waved his hand in the air and told her to go find more documents, ushering her back into the endless bureaucratic loop that is India’s legal system. Most of the others received similar treatment.

Later, we asked him what the police were doing to combat the Maoists. When the police go on missions now, he told us, they pass out literature to the mostly illiterate peasantry and staple on every tree slogans warning people away from Maoism. “We don’t only go into the forest to kill people,” he bragged. “We also hang posters.”

Death and Madness at Diamond Mountain

For Playboy

People come from all over the world to Arizona’s Diamond Mountain University, hoping to master Tibetan teachings and achieve peace of mind. For some, the search for enlightenment can go terribly wrong.

Ian Thorson was dying of dehydration on an Arizona mountaintop, and his wife, Christie McNally, didn’t think he was going to make it. At six in the morning she pressed the red SOS button on an emergency satellite beacon. Five hours later a search-and-rescue helicopter thumped its way to the stranded couple. Paramedics with medical supplies rappelled off the hovering aircraft, but Thorson was already dead when they arrived. McNally required hospitalization. The two had endured the elements inside a tiny, hollowed-out cave for nearly two months. To keep the howling winds and freak snowstorms at bay, they had dismantled a tent and covered the cave entrance with the loose cloth. Fifty yards below, in a cleft in the rock face, they had stashed a few plastic tubs filled with supplies. Even though they considered themselves Buddhists in the Tibetan tradition, an oversize book on the Hindu goddess Kali lay on the cave floor. When they moved there, McNally and Thorson saw the cave as a spiritual refuge in the tradition of the great Himalayan masters. Their plan was as elegant as it was treacherous: They would occupy the cave until they achieved enlightenment. They didn’t expect they might die trying.

Almost irrespective of the actual spiritual practices on the Himalayan plateau, the West’s fascination with all things Tibetan has spawned movies, spiritual studios, charity rock concerts and best-selling books that range from dense philosophical texts to self-help guides and methods to Buddha-fy your business. It seems as if almost everyone has tried a spiritual practice that originated in Asia, either through a yoga class, quiet meditation or just repeating the syllable om to calm down. For many, the East is an antidote to Western anomie, a holistic counterpoint to our chaotic lives. We don stretchy pants, roll out yoga mats and hit the meditation cushion on the same day that we argue about our cell phone bill with someone in an Indian call center. Still, we look to Asian wisdom to center ourselves, to decompress and to block off time to think about life’s bigger questions. We trust that the teachings are authentic and hold the key to some hidden truth. We forget that the techniques we practice today in superheated yoga studios and air-conditioned halls originated in foreign lands and feudal times that would be unrecognizable to our modern eyes: eras when princely states went to war over small points of honor, priests dictated social policy and sending a seven-year-old to live out his life in a monastery was considered perfectly ordinary.

Yoga, meditation, chakra breathing and chanting are powerful physical and mental exercises that can have profound effects on health and well-being. On their own they are neither good nor bad, but like powerful lifesaving drugs, they also have the potential to cause great harm. As the scholar Paul Hackett of Columbia University once told me, “People are mixing and matching religious systems like Legos. And the next thing you know, they have some fairly powerful psychological and physical practices contributing to whatever idiosyncratic attitude they’ve come to. It is no surprise people go insane.” No idea out of Asia has as much power to capture our attention as enlightenment. It is a goal we strive toward, a sort of perfection of the soul, mind and body in which every action is precise and meaningful. For Tibetans seeking enlightenment, the focus is on the process. Americans, for whatever reason, search for inner peace as though they’re competing in a sporting event. Thorson and McNally pursued it with the sort of gusto that could break a sprinter’s leg. And they weren’t alone. More than just the tragedy of obscure meditators who went off the rails in nowhere Arizona, Thorson’s death holds lessons for anyone seeking spiritual solace in an unfamiliar faith.

Until February 2012, McNally and Thorson were rising stars among a small community of Tibetan Buddhist meditators and yoga practitioners who had come to the desert to escape the scrutiny and chaos of the city in order to focus on spiritual development. McNally was a founding member of Diamond Mountain University and Retreat Center – a small campus of yurts, campers, temples and retreat cabins that sprawls over two rocky valleys adjacent to historic Fort Bowie in Arizona. In the past decade Diamond Mountain has risen from obscurity to become one of the best known, if controversial, centers for Tibetan Buddhism in the United States. Its supreme spiritual leader is Michael Roach, an Arizona native, Princeton graduate and former diamond merchant who took up monk’s robes in the 1980s and remains one of this country’s most enthusiastic evangelists for Tibetan Buddhism. McNally was Roach’s most devoted student, his lover, his spiritual consort and, eventually, someone he recognized as a living goddess. For 14 months McNally led one of the most ambitious meditation retreats in the Western world. Starting in December 2010 she and 38 other retreat participants pledged to cut off all direct contact with the rest of the planet and meditate under vows of silence for three years, three months and three days. Unwilling to speak, they wrote down all their communications. Phone lines, airconditioning and the Internet were off-limits.

The only way they could communicate with their families was through postal drops once every two weeks. The strict measures were intended to remove the distractions that infiltrate everyday life and allow the retreatants a measure of quiet to focus on the structure of their minds. Thorson’s death might have gone unnoticed by the world if, days after, Matthew Remski, a yoga instructor, Internet activist and former member of the group, had not begun to raise questions about the retreat’s safety on the well-known Buddhist blog Elephant Journal. He called for Roach to step down from Diamond Mountain’s board of directors and for state psychologists to evaluate the remaining 30-odd retreatants. His posting received a deluge of responses from current and former members, some of whom alleged sexual misconduct by Roach and made accusations of black magic and mind control.

Roach rose to prominence in the late 1990s after the great but financially impoverished Tibetan monastery Sera Mey conferred on him a geshe degree, the highest academic qualification in Tibetan Buddhism. Conversant in Russian, Sanskrit and Tibetan, he was an ideal messenger to bring Buddhism to the West and was widely acclaimed for his ability to translate complex philosophical ideas into plain English. He was the first American to receive the title, which ordinarily takes some 20 years of intensive study. In his case, he was urged by his teacher, the acclaimed monk Khen Rinpoche, to spend time outside the monastery, in the business world. At his teacher’s command, Roach took a job at Andin International Diamond Corporation, buying and selling precious stones. According to a book Roach co-authored with McNally, The Diamond Cutter: The Buddha on Managing Your Business and Your Life, in 15 years he grew the firm from a small-time company to a giant global operation that generated annual revenue in excess of $100 million. The book cites a teaching called “The Diamond Sutra,” in which the Buddha looks at diamonds, with their clarity and strength, as symbolic of the perfection of wisdom. But the diamond industry, particularly during the years Roach was active in it, is one of the dirtiest in the world – fueling wars in Africa and linked to millions of deaths.

During a lecture Roach gave in Phoenix last June, I asked him how he could reconcile his Buddhist ethics with making vast sums of money through violent supply chains. Roach stared at me with moist, sincere- looking eyes and avoided the question. “If your motivation is pure, then you can clean the environment you enter,” he said. “I wanted to work with diamonds. It was a 15-year metaphor, not a desire to make money. I wanted to do good in the world, so I worked in one of the hardest and most unethical environments.” It was the sort of answer that plays well with business clients. Rationalizations like this are not uncommon in industry, but they are for a Buddhist monk. If Roach was unorthodox, he was also indispensable. His business acumen might have been enough for some early critics to look the other way. His share of Andin’s profits was ample enough that he could funnel funds to Sera Mey to establish numerous charitable missions.

His blend of Buddhism and business made him an instant success on the lecture circuit, and even today he is comfortable in boardrooms in Taipei, Geneva, Hamburg and Kiev, lecturing executives on how behaving ethically in business will both make you rich and speeding the path of enlightenment. Ian Thorson had always been attracted to alternative spirituality, and he had a magnetic personality that made it easy for him to win friends. Still, “he was seeking something, and there was an element of that asceticism that existed long before he took to any formal practice of meditation, yoga and whatnot,” explains Mike Oristian, a friend of his from Stanford University. Oristian recounts in an email the story of a trip Thorson took to Indonesia, where he hoped a sacred cow might lick his eyes and cure his poor eyesight. It didn’t work, and Thorson later admitted to Oristian that “it was a long way to go only to have the feeling of sandpaper on his eyes.”

Roach gave Thorson a structure to his passion and a systematic way to think about his spiritual quest. After Thorson began studying Roach’s teachings in 1997, Oristian remembers, some of his spontaneous spark seemed to fade. Kay Thorson, Ian’s mother, had a different perspective. She suspected he had fallen under the sway of a cult and hired two anti-cult counselors to stage an intervention. In June 2000 they lured him to a house in Long Island and tried to get him to leave the group. “He was skinny, almost anorexic,” she says. They tried to show him he had options other than following Roach. For a time it seemed to work. Afterward he wrote to a friend about his family’s attempt to deprogram him: “It’s so weird that my mom thinks I’m in a cult and so does Dad and so does my sister. They talk to me in soft voices, like a mental patient, and tell me that the people aren’t ill-intentioned, just misguided.” For almost five years he traveled through Europe, working as a translator and tutor, but he never completely severed ties. Eventually he made his way back to Roach’s fold. In 1996, when she was only two years out of New York University, Christie McNally dropped any plans she’d had to pursue an independent career and became Roach’s personal attendant, spending every day with him and organizing his increasingly busy travel schedule. And though his growing base of followers didn’t know it, she would soon be sharing Roach’s bed.

The couple married in a secret ceremony in Little Compton, Rhode Island in 1998. As had many charismatic teachers before him, Roach established a dedicated following. As it grew he planned an audacious feat that would take him out of the public eye and at the same time establish him in a lineage of high Himalayan masters. He announced that, from 2000 to 2003, he would put his lecturing career on hold and attempt enlightenment by going on a three-year meditation retreat along with five chosen students, among them Christie McNally. In many ways, Roach’s silence was more powerful than his words. Three years, three months and three days went by, and Roach’s reputation grew. Word of mouth about his feat helped expand the patronage of Diamond Mountain and the Asian Classics Institute, which distributed his teachings through audio recordings and online courses.

Every six months he emerged to teach breathless crowds about his meditating experiences. At those events he was blindfolded but spoke eloquently on the nature of emptiness. Finally, on 16 January 2003 he dropped two bombshells in a poem he addressed to the Dalai Lama and published in an open letter. In his first revelation he claimed that after intensive study of tantric practices he had seen emptiness directly and was on the path to becoming a bodhisattva, a sort of Tibetan angel. The word tantra derives from Sanskrit and indicates secret ritualized teachings that can be a shortcut to advanced spiritual powers. The second revelation was that while in seclusion he had discovered that his student Christie McNally was an incarnation of Vajrayogini, the Tibetan diamond-like deity, and that he had taken her as his spiritual consort and wife. They had taken vows never to be more than 15 feet from each other for the rest of their lives and even to eat off the same plate. In light of her scant qualifications as a scholar, Roach legitimized McNally by bestowing her with the title of “lama,” a designation for a teacher of Tibetan Buddhism.

These revelations severely split the Tibetan Buddhist community. The reprimands were swift and forceful. Several respected lamas demanded that he hand back his monk’s robes. Others, including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, who heads the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, a large and wealthy group of Tibetan Buddhists, advised that he prove his claims by publicly showing the miraculous powers that are said to come with enlightenment – or be declared a heretic. That Zopa Rinpoche was one of Roach’s greatest mentors made the criticism all the more pertinent and scathing. Robert Thurman, a professor of religious studies at Columbia University, met with Roach and McNally shortly after Roach published his open letter. He was concerned that Roach had broken his vows and that his continuing as a monk could damage the reputation of the larger Tibetan Buddhist community. “I told him, ‘You can’t be a monk and have a girlfriend; you have clearly given up your vow,’” Thurman says. “To which he responded that he had never had genital contact with a human female. So I turned to her and asked if she was human or not. She said right away, ‘He said it. I didn’t.’ There was a pregnant pause, and then she said, ‘But can’t he do whatever he wants, since he has directly realized emptiness?’” On the phone I can hear Thurman consider his words and sigh. “It seemed like they had already descended into psychosis.”

Intensive retreats where monks meditate in isolated caves are mainstays of Buddhism in Tibet, where they are typically used to establish the credentials of an important teacher. However, such retreats make less sense outside Tibet’s historically feudal world. The human mind is reasonably fragile, and isolation can act like an echo chamber. For the retreatants, Diamond Mountain was a ritualized place where they could try to sharpen their minds to see as little of the ordinary world as possible and allow their visualizations to be the focus of their daily life. For better or worse, Roach and McNally emerged from their first great retreat as different people than when they began. Much of the explanation for this comes down to physical changes in the brain. In its purest form meditation is a way to look at the mind in isolation. By calming the body and watching thoughts come and go, an experienced meditator can uncover astonishing things in his or her physiology and psychology. Meditation is a little like putting your mind in a laboratory and seeing what it does on its own. Although everyone’s experience is different, it is common to see walls shift, hear noises that aren’t there, observe changes in the quality of light or have time inexplicably speed up or slow down. Neuroscientists have discovered that over the long term meditating can cause changes in the composition of brain matter, and even short stints can create significant physical alterations in one’s neurological makeup.

Whatever changes occur during short, daily meditations are only amplified on silent retreats. Although comprehensive clinical studies on the potential adverse side effects of such retreats are just getting under way (one led by Willoughby Britton, a neuroscientist at Brown University, is in its second year), it is clear that some people find the isolation and mental introspection too intense. Some lose touch with reality or fall into psychotic states. The world generally embraces meditation as a method of self-help, but a 1984 study by Stanford University psychologist Leon Otis of 574 subjects involved in Transcendental Meditation (one of the more benign forms)showed that 70 percent of longtime meditators displayed signs of mental disorders. Another explanation is that our expectations for meditation are often too grand. From a young age we are steeped in tales of superheroes and jedis who are able to perform great feats through their innate specialness and intensive study. We hear stories of levitating yogis and the power of chakras, tai chi and badass Shaolin monks, and quietly think to ourselves that maybe anything is possible.

McNally’s speedy elevation to Vajrayogini and lama mirrors those nascent desires. For those who aren’t instantly anointed, the religion offers a clear method: Meditate often, keep your vows and, if you’re in a hurry, start practicing tantra. From a certain standpoint Roach’s approach was a success. Members of the group noted that during the period when Roach and McNally were in a relationship, attendance at events and lectures was never higher. They taught together, and their mutual confidence and earnestness seemed to be an open door to enlightenment. If it was okay to take a spiritual partner along for the ride, couples could join and work on their spiritual practice together instead of following the more orthodox custom of practicing alone.

After the 2003 retreat, Roach and McNally continued to forge a spiritual path that, to outside observers, looked less like Tibetan Buddhism and more like a new faith that mixed elements of Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity and good oldfashioned showmanship. They co-authored half a dozen books on Tibetan meditation, yoga and business ethics, one of which attained best-seller status. Sid Johnson, a musician who was briefly on the board of directors of Diamond Mountain, worried that the group was becoming too focused on magical thinking. His concerns came to a head in 2005 during a secret initiation into the practice of the bull-headed tantric deity Yamantaka, whose name translates as “destroyer of death.” As part of a four-day ritual, all the initiates had to meet privately with Geshe Michael and Lama Christie, as their students called them, in a yurt for their final empowerment, which would help them conquer death. Johnson was nervous when he entered the room wearing a blindfold and heard Roach ask him to lie down on their bed. When he did so, McNally started to massage his chakras, starting with his head and ending at his penis. “I’m not sure who undid my pants, but it was part of the blessing,” says Johnson. When they were done, he sat up – still wearing the blindfold – and felt McNally’s lips pressing against his. They kissed. “There is a part of the initiation when your lama offers you a consort, and the way Geshe Michael teaches it, the things that happen in the metaphysical world also have to happen in the real one,” says Johnson. Afterward, he says, they all giggled like children at a summer camp, as though they were breaking taboos and no one else would know. Ten minutes later Johnson left and they asked Johnson’s wife to come in alone. Altogether, almost 20 students had private initiation by the couple that night.

By most accounts McNally began to take center stage in the spiritual road show. It was as though Roach was stepping back and allowing his partner to teach philosophy and meditation in his stead. “He seemed distracted and unengaged whenever she would speak, just staring at the ceiling while she was talking, as if distancing himself from whatever Christie was saying,” says Michael Brannan, another longtime student and current full-time volunteer at Diamond Mountain. “He called her Vajrayogini. Can you imagine being promoted to deity by your spouse and guru?” Even though she was a lama, McNally wanted to prove she could be a leader on her own. She pressed for a second great retreat, this one even more ambitious than the first. Instead of only a few humble yurts on a desolate property, they would build dozens of highly efficient self-cooling solar-powered structures – permanent infrastructure on Diamond Mountain property that could host scores of retreatants for long periods. Roach and McNally planned to lead 38 people into the desert on a quest to see emptiness directly. They had no problem finding followers to foot the bill. Participants were required to build and pay for their own cabins, with the expectation that when they were done with their retreat, ownership of the cabins would revert to Diamond Mountain. Modestly priced cabins cost around $100,000, while more lavish spaces hovered closer to $300,000. Volunteers and contractors labored on the designs for several years while Roach and McNally prepped the spiritual seekers with philosophy and meditation techniques.

By the middle of 2010, plans for the second great retreat were coming together, but Roach and McNally’s relationship was falling apart. The reasons for the split are unclear. Members of the group speak about illicit sexual liaisons between Roach and other students and covert theological power struggles. No one knows for sure, and neither Roach nor McNally commented on the split for this story, but the fallout reverberated through the community. Michael Brannan remembers “a lot of people just sort of swapped partners,” including McNally. Former member Ekan Thomason remembers that Thorson dropped off his then girlfriend at her house with a sleeping bag and disappeared into the desert. The next time Thomason saw Thorson, he and McNally were dancing under a disco ball at a party at the Diamond Mountain temple. In October 2010 McNally and Thorson married in a Christian ceremony in Montauk, New York. Faced with being confined on a silent retreat with his ex-wife, Roach quietly backed away from his commitment to participate and gave over leadership of the affair to McNally. For McNally the second great desert retreat would be a major testing ground for her as a spiritual leader. At its conclusion she would have had almost seven years of silent meditation under her belt, a qualification few Buddhist practitioners – even in Tibet – can claim. With 38 people looking to her for spiritual guidance, including a new husband for whom she was guru, goddess and wife, she needed to impart something special. She found her answer outside Tibetan Buddhism, in the Hindu goddess Kali.

Kali isn’t an ordinary member of the Hindu pantheon. Although a few major temples, including the famous Dakshinewar Kali Temple in Calcutta, are devoted to her worship, most mainstream Hindus invoke her name only in times of violence or war. In the 1700s British colonialists popularized and exaggerated stories of Kali worshippers called thuggee (from which we get the English word thug), who murdered unsuspecting travelers on isolated roads and used their bodies in sacrifices to the goddess to gain magical powers. The few Hindus steeped in tantric practice – usually quite different from Buddhist tantra – will sometimes appeal to Kali for female spiritual power, called Shakti. Although Kali is considered untamable, wild and dangerous, it seems McNally wanted to add the goddess to her tantric meditation in order to speed her journey to enlightenment.

In October 2009 McNally staged a 10-day Kali initiation with more than 100 prospective devotees. She decorated the temple with weapons: swords, guns, crossbows, chain saws and menacing-looking garden implements meant to show the violent side of the deity. In a symbolic rite reminiscent of India’s now-banned thuggee cult, members were “kidnapped” on the road between holy sites and stuffed into a small wooden box to heighten their fear. Roach held his own version of the ritual nearby as Ekan Thomason met Lama Christie in a structure called Lama Dome. There, McNally gave her a medical lancet. “Kali requires something from you. She requires your blood,” McNally said, reminding Thomason of a beautiful swashbuckling pirate as she ran a finger across the sharp edge of the knife. The ceremony was designed to be terrifying, and participants were split in their reactions. Some had accepted McNally as an infallible teacher and hoped to learn despite the theatrics. Others worried that Diamond Mountain was turning toward a dark, occult version of Hinduism. But a year later almost 40 retreatants would lock themselves in a valley under Lama Christie’s sole spiritual direction. In the months leading up to the retreat in 2010 the group showed signs of stress as members became increasingly confused between the spiritual world they were trying to access through meditation and the real world, where actions had predictable consequences.

Under Roach and McNally’s direction they threw parties in the temple at which they served “nectar,” specially blessed booze they could drink despite their vows of abstinence. At one of these parties some members, who wish to remain anonymous, say they saw Roach and McNally perform miracles – allegedly walking through a wall of the temple building by bending the laws of space and time. Such stories became commonplace around the camp, and the communal hysteria vaulted Roach and McNally to godlike status. Joel Kramer and Diana Alstad, co-authors of The Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power, explain these perceived miracles on a psychological level. Kramer says, “People can convince themselves they have seen many things that are really just projections of their own mind.” Alstad adds that disciples give their mental energy to a guru and the guru reflects the energy back to them. It seems likely that McNally learned to see the world through Roach’s lens. “Roach took her mind over – or she gave it to him,” says Alstad. “That’s what followers do: They totally surrender. She surrendered to him as a young, unformed woman. And a similar process was probably reversed between Thorson and McNally. She was his lama, his guru and his wife.”

When the retreat started, no one had much of an idea how their relationship would hold up. Then, in March 2011, after three months of silence, Thorson knocked on the door of a retreatant who was a nurse practitioner. He was bleeding profusely from three stab wounds. She was afraid to treat him and recommended he go to a hospital. But the second person to see him, a doctor on retreat, reluctantly tended to the slashes on his torso and shoulder. The wounds were so deep, the doctor said, they “threatened vital organs.” At the time, McNally and Thorson gave no explanation for how it happened, but soon rumors of domestic abuse began to circulate in the same hushed whispers as the talk about Roach’s supposed sexual liaisons with various students. With most people under vows of silence, it is no surprise that almost a year passed before the event became publicly known. In February 2012, Lama Christie recused herself from her vow of silence to give a public lecture on her realizations during meditation. Wearing her trademark white robes and with a silken blindfold across her eyes, she sat on a throne and talked about the spiritual lessons she had learned while grappling with an increasingly unstable and violent relationship.

In an act she described as playful, McNally said she stabbed Thorson three times with a knife they had received as a wedding present. He could have died in the exchange, and few people in the crowd could grasp what the lesson was supposed to mean. Could violence be a route to their ultimate spiritual goals? Had their teacher gone crazy? Referencing her newfound grasp of the goddess Kali, she asked the crowd to learn from her experience with violence. Although the original recording of her talk has been taken off the Internet, she later explained the incident in a public letter: “I simply did not understand that the knife could actually cut someone… I was actively trying to raise up this aggressive energy, a kind of fierce divine pride… It was all divine play to me.” She went on to write about the tantric lessons Kali had taught her through the event and how she was trying to cope with occasional violence in her relationship with Thorson.

Jigme Palmo, a nun who sits on Diamond Mountain’s board of directors, stated later that the board was worried the focus on violence might spur other meditators down a dangerous path. The directors immediately convened emergency meetings and discussed various plans of action. “It was an impossible situation,” says Palmo. “We didn’t know what was happening inside the retreat, and yet the board was ultimately responsible if something went wrong.” They consulted a lawyer and sent urgent written messages to McNally asking for more information about domestic violence and her increasingly erratic decisions. Suddenly aware that her teachings had created a rift in the community, McNally tried to shore up her control of the meditators by banning all correspondence with the outside world. She ordered that all mail deliveries cease and instructed the retreatants to refuse contact with their families. The board members decided they had no choice but to act unilaterally to remove McNally from her role as teacher and to remove McNally and Thorson from the retreat itself. The board sent them a letter explaining their decision and gave McNally and Thorson an hour to pack their things and leave, offering to cover their relocation expenses, including hotel costs, a rental car, prepaid cell phones and $3,600 cash. The message was clear: Get out now.

But McNally and Thorson had taken vows to stay in Diamond Mountain’s consecrated area, and they had a different plan. Instead of leaving, McNally and Thorson planned to find a nearby cave where they could continue to meditate and still have contact with some of McNally’s students. Before they made their final arrangements to leave, McNally met privately with Michael Brannan to discuss the board’s decision. McNally kept her vow of silence, and the two passed notes back and forth, creating an effective transcript of her thoughts at the time. The document, which Brannan shared with me, sheds light on McNally’s state of mind. In it she mentions ordinations that took place and the pressure that people – especially Thorson – felt while they were “locked up” on retreat. But it all also fit into a broader plan. “Everything is perfect, you’ll see” she begins, adding, “I have inherited my holy lama’s [Roach’s] style of pushing people past their breaking point.” She blames her former husband for having “stoked the fire” and making people fear her as a teacher.